Shoulder Biomechanics, Part I: The Subscapularis Muscle

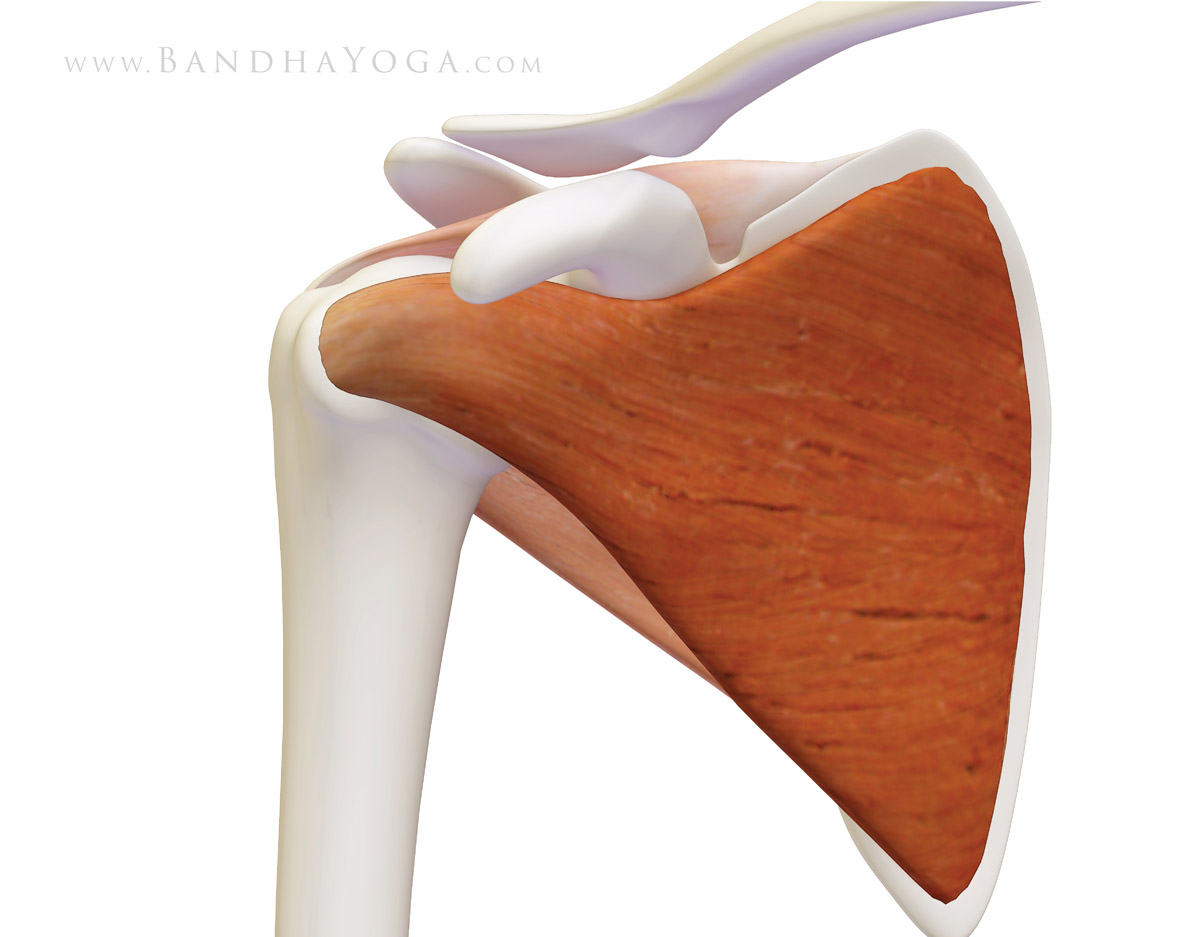

This is the first of a four-part series on the shoulder joint, focusing specifically on the rotator cuff and its biomechanical relationship with the deltoid muscle. Let's begin by looking at the muscles that comprise the rotator cuff, starting with the subscapularis. As figure 1 illustrates, the subscapularis occupies the space, or fossa, at the front of the scapula. From there it attaches to the lesser tuberosity, a knob-like structure on the humerus bone at the front of the shoulder. Concentrically contracting the subscapularis muscle (shortening the muscle on contraction) internally rotates the shoulder. The subscap also acts, in conjunction with the infraspinatus muscle, as a stabilizer of the humeral head in the socket (glenoid). We test strength and function of this muscle with the "bellypress" test or the "bear hug" test. Tightness in the subscapularis can limit external rotation of the shoulder.

|

| Figure 1: The subscapularis muscle, illustrating the origin on the inside of the scapula and the insertion on the lesser tuberosity of the humerus. |

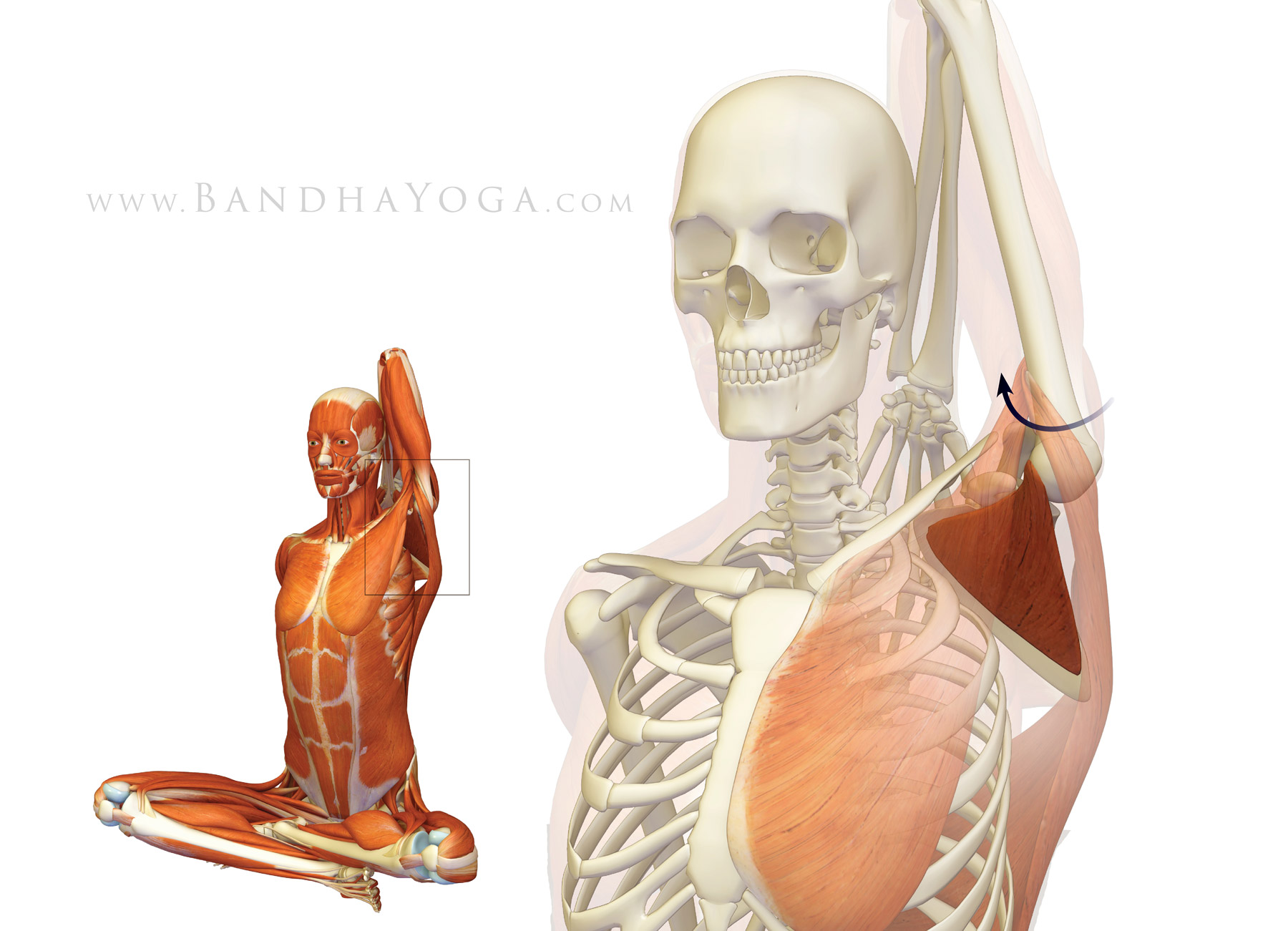

Figure 2 illustrates one of the poses that stretch the subscapularis muscle, namely, Gomukhasana. The upper side humerus externally rotates in this pose, thus stretching the muscle as shown.

|

| Figure 2: This illustrates the effect on the subscapularis muscle of the upper arm in Gomukhasana. External rotation of the humerus stretches the muscle. |

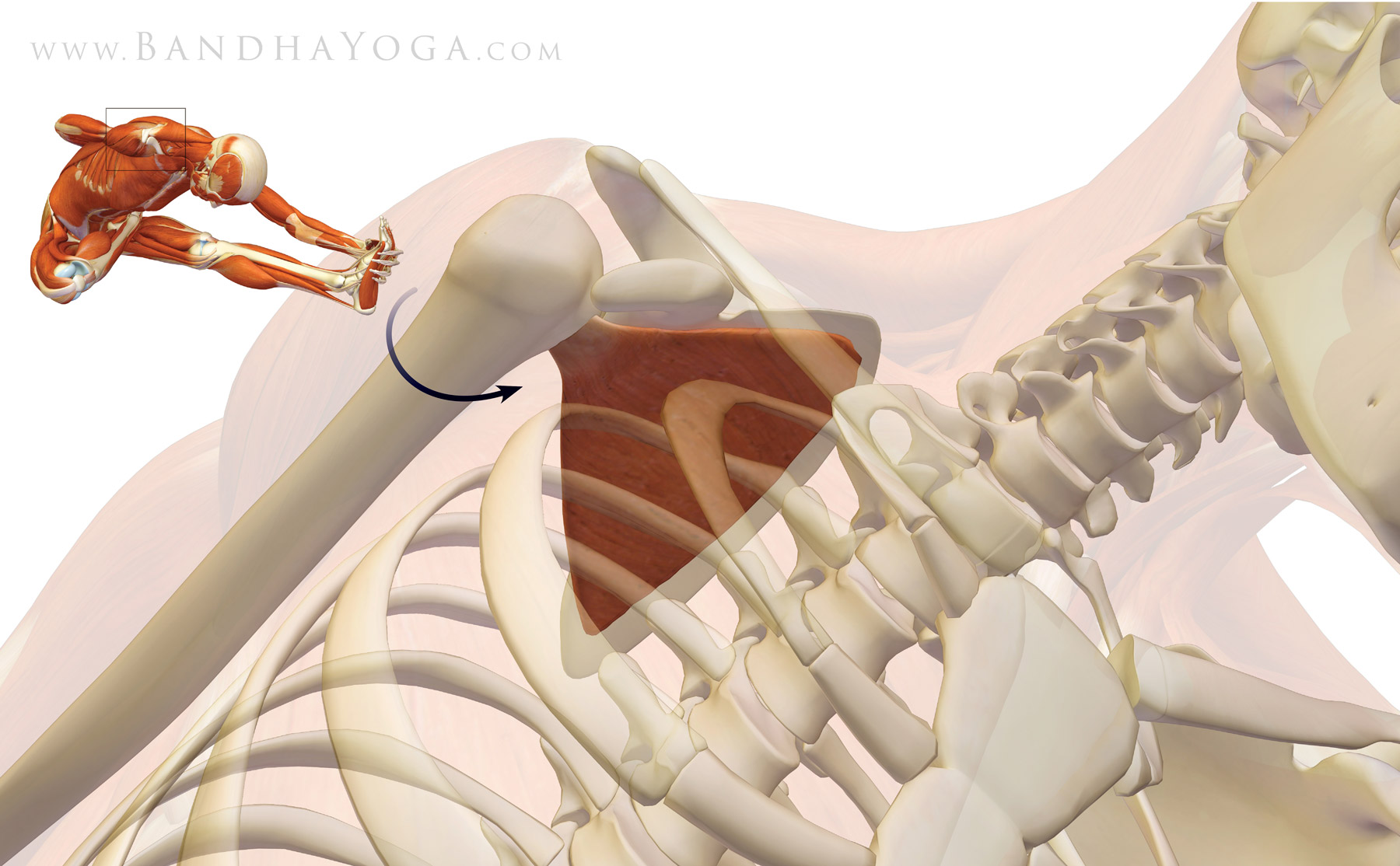

Figure 3 illustrates engaging the subscapularis muscle in Ardha Baddha Padma paschimottanasana. Advanced practitioners can attempt to lift the hand off the back to engage the muscle in this pose. This also replicates the "liftoff" test, which is used in orthopedics to test the function of the subscap muscle.

|

| Figure 3: This image illustrates contraction of the subscapularis muscle to internally rotate the humerus. |

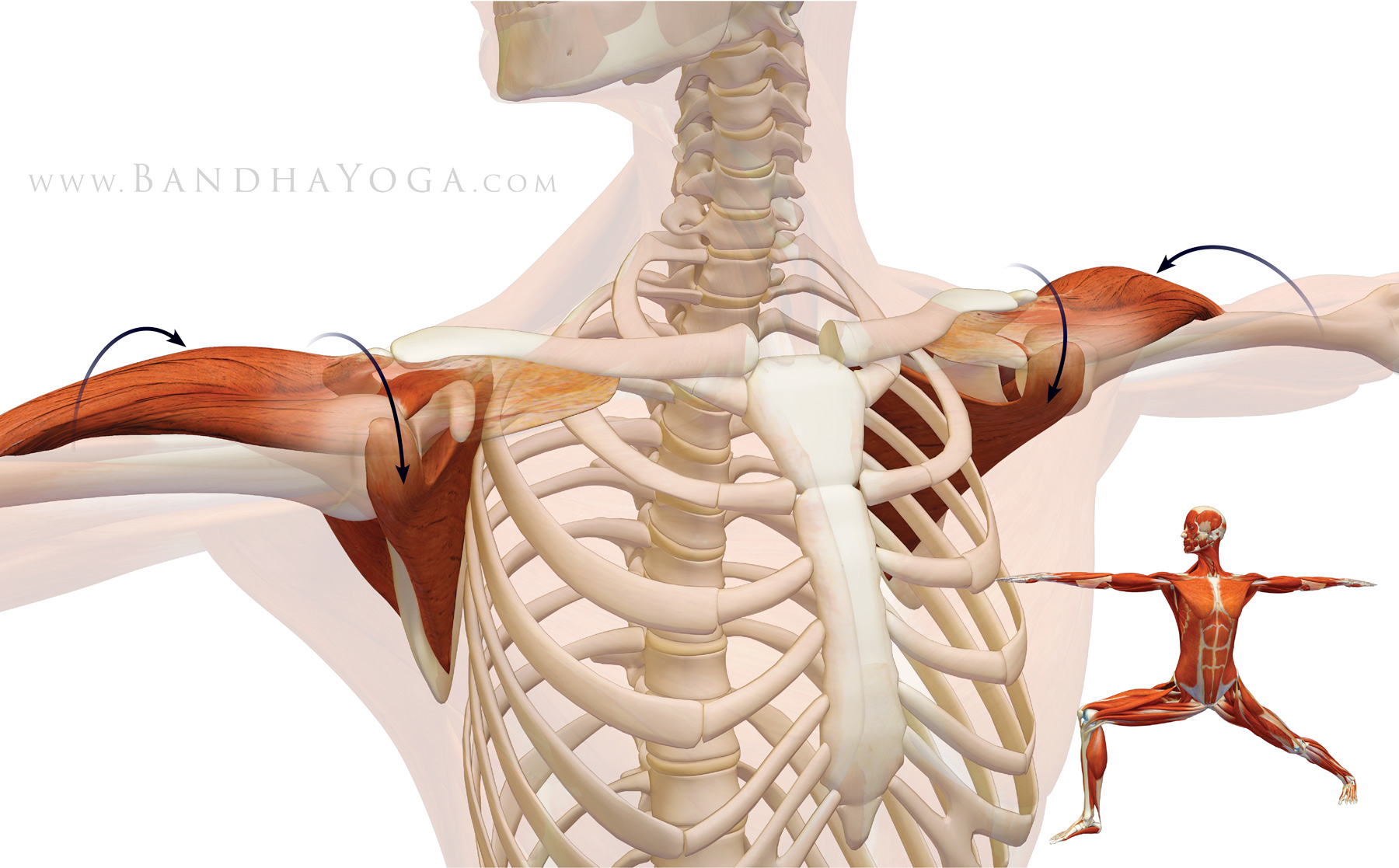

Finally, we have the subscapularis as a stabilizer during a static position in a pose. In Warrior II, attempt to internally rotate the shoulders by imagining pressing the mound at the base of the index fingers down against an object. Resist this by externally rotating the shoulders at the same time. Co-contracting opposing muscles--like the subscap and infraspinatus--stabilizes the head of the humerus in the socket while the deltoid contracts to abduct the humerus. Click here to go into a bit more depth on the subject of stabilizing your shoulders in your Downward dog pose.

|

| Figure 4: Co-contracting the subscapularis and the infraspinatus stabilizes the humeral head in the socket while the deltoid muscle abducts the humerus. |

Stabilizing Your Shoulders In Downward Dog

In our last post, we discussed joint rhythm for the shoulders. In this blog post I want to share some of my recent investigations on the biomechanics of the shoulder joint, with some specific tips for Down Dog. Shoulder pain is one of the problems that comes up in yoga, especially with folks who are doing Vinyasa based practice. The underlying cause of the pain can be multifactorial, but it is frequently related to impingement of the rotator cuff and subsequent inflammation of the cuff tendon (specifically the supraspinatus muscle). Inflammation of the tendon, in turn, affects function of the shoulder. Weakness or instability in the shoulder can then lead to abnormal pressures at the wrist, causing pain there as well. Thus, stabilizing the shoulders has beneficial effects beyond the shoulders. is a complex process involving strengthening the core and then linking the strong core to the shoulders.

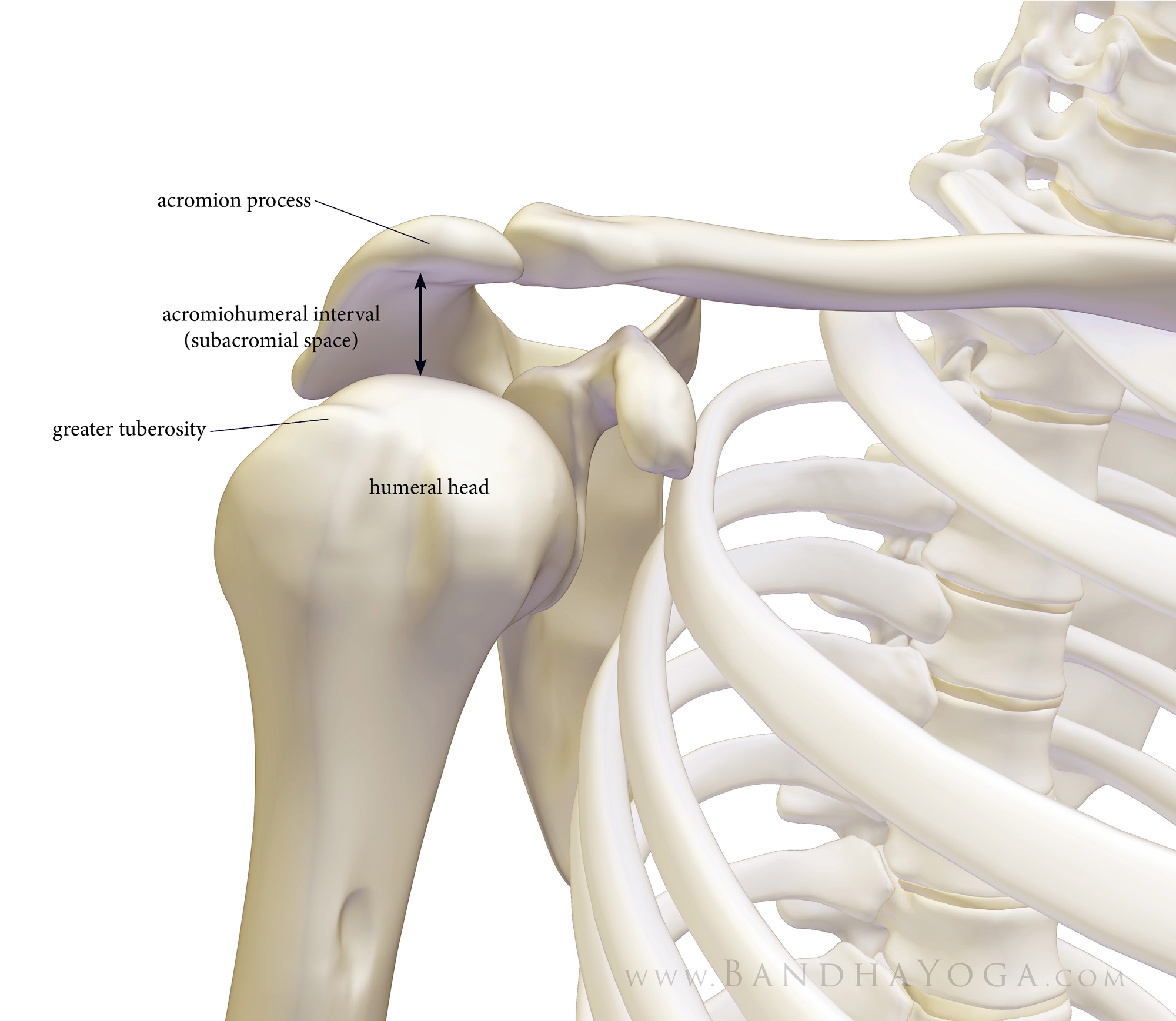

With this in mind, let’s look at one of the key factors in shoulder impingement, namely, the acromio-humeral interval. This refers to the distance between the undersurface of the acromion and the humeral head, as measured using radiology intruments (x-ray, ultrasound, mri). The acromion is a shelf of bone on the scapula, above the spine (seen in Figure 1). It serves as the attachment for the deltoid muscle. The humeral head articulates with the shoulder joint and serves as the attachment for the muscles of the rotator cuff (on the greater and lesser tuberosities). Factors that decrease the space between the acromion and humeral head can lead to inflammation of the cuff tendon due to compression between the two bones.

Research has shown that contracting the main adductor muscles of the shoulder serves to increase the acromio-humeral distance. These include the pectoralis major and latissimus dorsi. Co-contracting the biceps and triceps muscles when the arms are overhead can also draw the humerus away from the glenoid, as shown in Figure 2. Finally, externally rotating the shoulder humerus moves the vulnerable area of the supraspinatus tendon away from the area where it would impinge on the acromion (click here to learn more).

Here’s the cue…

Warm up first a bit. Then, take Downward Dog pose. I use three steps for the shoulders. Go slowly and use gentle engagements.

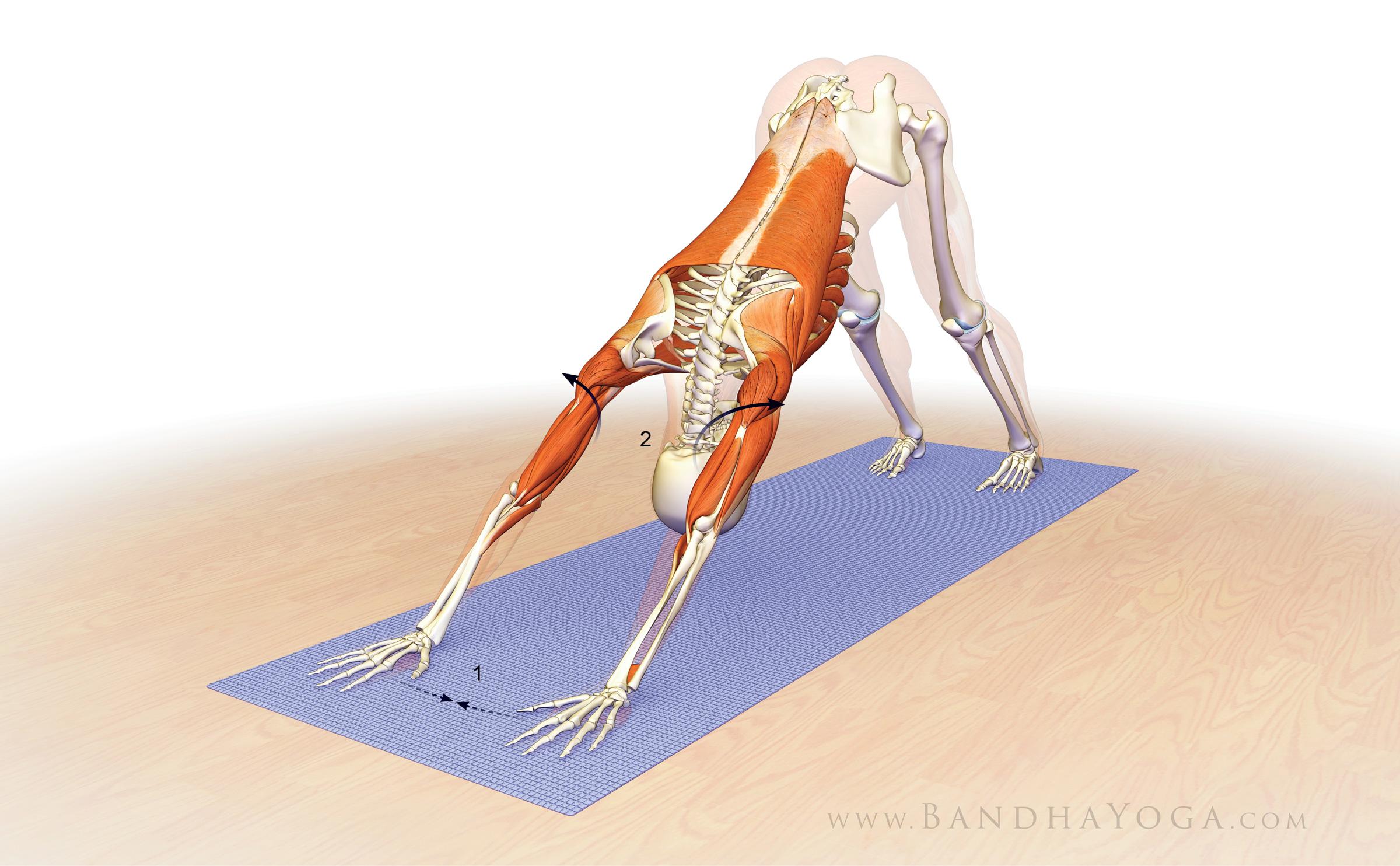

Figure 3 illustrates the various muscles involved in these cues.

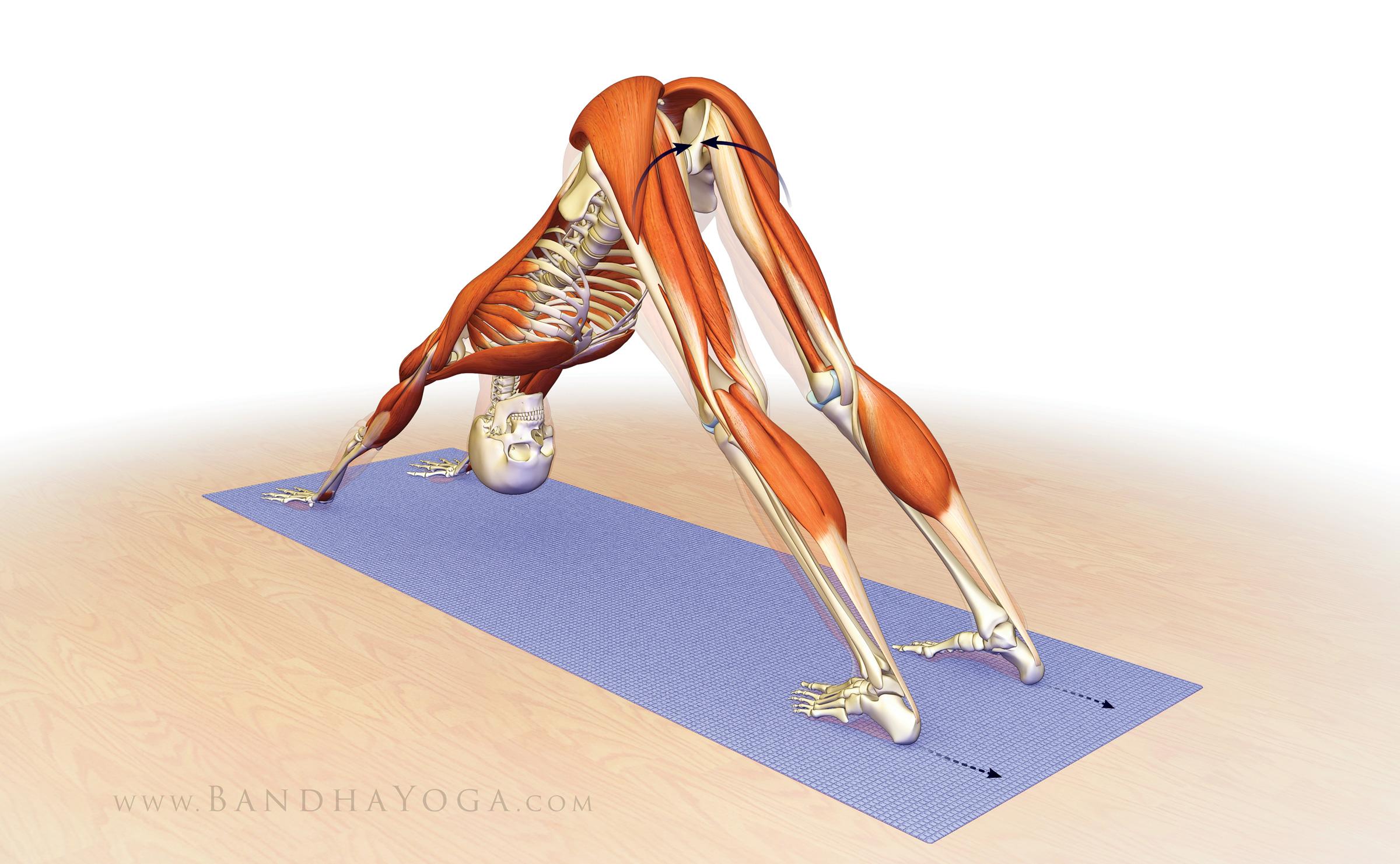

As a final adjustment, I like to link the action of the shoulders to the lower extremities. The cue for this is to engage your lower gluteus max and adductor magnus muscles by drawing in with the upper inner thighs and then attempt to drag your feet away from the hands. Feel how this stabilizes your pose. See Figure 4 for the graphics.

Bear in mind that shoulder stability is a complex process. The shoulders are linked to the core; so building a strong core leads to stable shoulders. Stable shoulders help to protect the wrists, and so on.

With this in mind, let’s look at one of the key factors in shoulder impingement, namely, the acromio-humeral interval. This refers to the distance between the undersurface of the acromion and the humeral head, as measured using radiology intruments (x-ray, ultrasound, mri). The acromion is a shelf of bone on the scapula, above the spine (seen in Figure 1). It serves as the attachment for the deltoid muscle. The humeral head articulates with the shoulder joint and serves as the attachment for the muscles of the rotator cuff (on the greater and lesser tuberosities). Factors that decrease the space between the acromion and humeral head can lead to inflammation of the cuff tendon due to compression between the two bones.

|

| Figure 1: The acromio-humeral interval. |

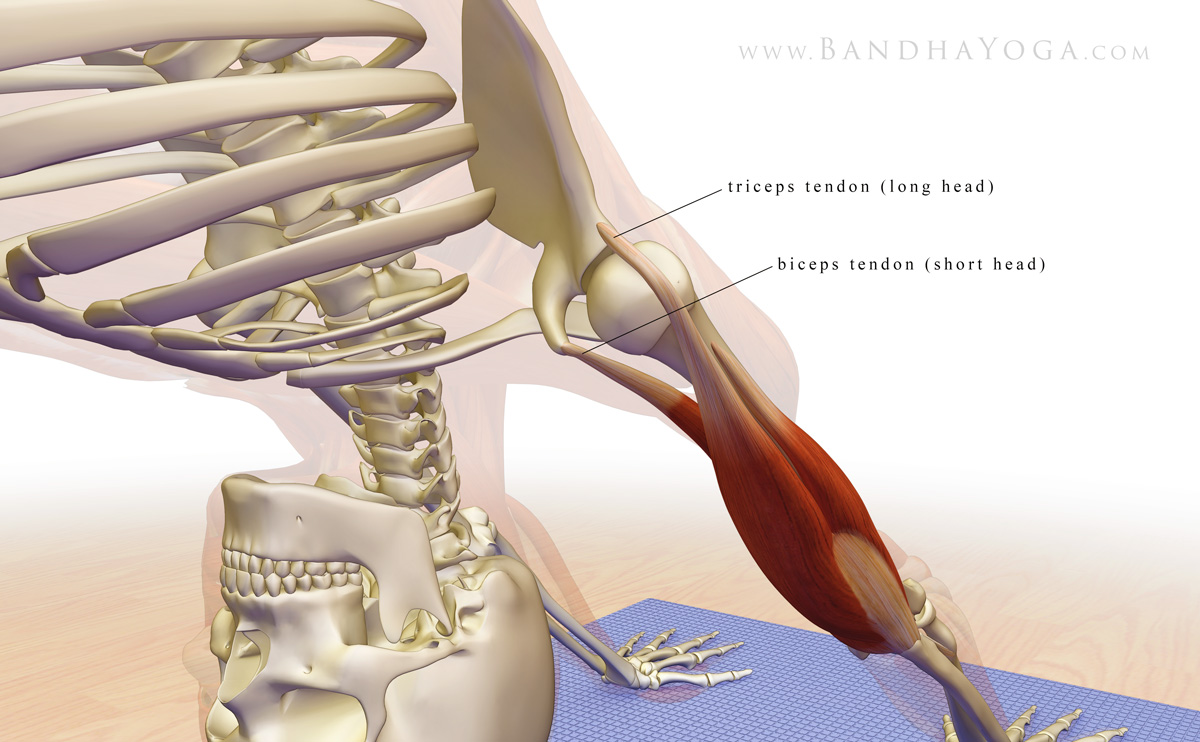

Research has shown that contracting the main adductor muscles of the shoulder serves to increase the acromio-humeral distance. These include the pectoralis major and latissimus dorsi. Co-contracting the biceps and triceps muscles when the arms are overhead can also draw the humerus away from the glenoid, as shown in Figure 2. Finally, externally rotating the shoulder humerus moves the vulnerable area of the supraspinatus tendon away from the area where it would impinge on the acromion (click here to learn more).

|

| Figure 2: The long head of the triceps and short head of the biceps in relation to the gleno-humeral joint with the arms overhead. |

Here’s the cue…

Warm up first a bit. Then, take Downward Dog pose. I use three steps for the shoulders. Go slowly and use gentle engagements.

- Contract the triceps to straighten your elbows. Then, press the mound at the base of your index fingers into your mat to engage the forearm pronator muscles.

- Next, fix your palms into the mat and try to drag the hands towards each other. This engages the adductor muscles of the shoulders as well as the biceps.

- Finally, gently roll the shoulders outward. This externally rotates the humerus bone and helps to bring the greater tuberosity away from the undersurface of the acromion.

Figure 3 illustrates the various muscles involved in these cues.

|

| Figure 3: Attempt to drag the hands towards one another. This engages the shoulder adductors. Then externally rotate the shoulders. |

As a final adjustment, I like to link the action of the shoulders to the lower extremities. The cue for this is to engage your lower gluteus max and adductor magnus muscles by drawing in with the upper inner thighs and then attempt to drag your feet away from the hands. Feel how this stabilizes your pose. See Figure 4 for the graphics.

|

| Figure 4: Engage the lower parts of the gluteus maximus and adductor magnus as you attempt to drag the feet away from the hands to stabilize the pose. |

Bear in mind that shoulder stability is a complex process. The shoulders are linked to the core; so building a strong core leads to stable shoulders. Stable shoulders help to protect the wrists, and so on.